|

Nicolai Fechin (pronounced "fay-shin") was born in 1881 in the town of Kazan, Russia. His father was highly skilled in woodworking and whom Fechin received early instruction in drawing and sculpting. In 1895, at the age of 13, Fechin enrolled in the Art School of Kazan, a branch of the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. Operated by graduates of the Academy, the school promoted individual development within an academic framework of Russian literature, art history, and architecture.

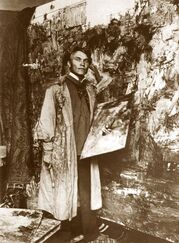

After graduating from the Kazan school in 1900, Fechin entered the Imperial Academy of Arts. There he studied under the tutelage of painter Ilya Repin, whose highly popular works emphasized the realistic values of northern European masters such as Rembrandt. After 1904, he began to concentrate increasingly on portraiture. Fechin also began to experiment with using the palette knife to apply color to large areas of the painting surface and to emphasize gesture and movement. |

After traveling in Siberia with a geologist friend in the summer of 1904, Fechin spent the following summer visiting the smaller villages in the vicinity of Kazan to observe and record the everyday life of the local peasant farmers. His fascination with rural customs and native people found expression again some twenty years later among the indigenous inhabitants of northern New Mexico .

|

Fechin graduated from the academy in St. Petersburg in 1908 and was awarded the Prix de Rome scholarship that enabled him to travel outside Russia to visit museums and art galleries in Austria, Germany, Italy, and France. Returning to Kazan from Paris in the late fall of 1909, he accepted a full-time position as an instructor at the local art school. In 1910 he won a gold medal for painting at the annual International Exhibition in Munich and was invited to show in the International Exhibition held at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, that same year. Here his work came to the attention of New York art patron W.S. Stimmel, through whom Fechin began selling paintings in the United States.

|

In 1911, Fechin married Alexandra Belkovitch, the daughter of the director of the art school in Kazan. In 1914 the couple's only child, Eya, was born. WW1 broke out, then, following the abdication of the Czar and the establishment of a revolutionary government in Moscow, Russia entered a period of social upheaval and intermittent civil war. The collapse of law and order and widespread shortages of food, medicines, and other necessities rendered Russian life chaotic. Fechin's parents died of typhoid fever. Fechin moved his family to Vasilievo, thirty miles from Kazan, where Alexandra's father had purchased a house for them. Living in the country was somewhat safer for them and gave Alexandra the opportunity to grow some vegetables and have chickens. Fechin would teach during the week and travel to see his family on weekends.

Conditions at the school began to deteriorate. There was no heat in the buildings and painting supplies became increasingly hard to find or of poor quality. In 1920, Fechin met Americans with the American Relief Administration who had come to Russia to distribute food supplies. They told him how much better life in the US could be for his family and his career.

Conditions at the school began to deteriorate. There was no heat in the buildings and painting supplies became increasingly hard to find or of poor quality. In 1920, Fechin met Americans with the American Relief Administration who had come to Russia to distribute food supplies. They told him how much better life in the US could be for his family and his career.

|

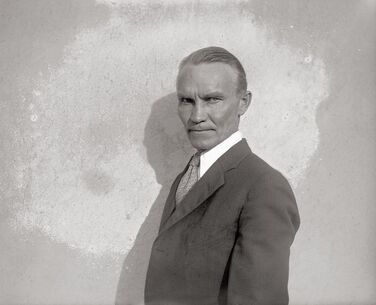

In 1922 Stimmel initiated the process that eventually enabled the Fechins to immigrate to the United States. After many delays, caused for the most part by governmental red tape, the Fechins arrived in New York City on August 1, 1923. At forty-two years of age, having left everything he had ever known, Fechin faced the uncertain prospect of creating a new life in a new country.

With the help of friends and patrons such as Stimmel and financier John Burnham, who at |

one time owned the largest collection of Fechin's work, Fechin settled into a studio apartment off Central Park and almost immediately obtained a number of important portrait commissions. He also began teaching classes at the Grand Central School of Art and exhibiting at the National Academy of Design, where in 1924 he won the coveted Thomas Proctor prize for portraiture. Soon after, he began exhibiting regularly at the Grand Central Art Gallery downtown.

Despite his growing reputation and the obvious advantages of working in New York, Fechin found it hard to adjust to the pace of life in the metropolis. During his fourth year in America, he developed tuberculosis and on his doctor’s advice began a search for a more healthful climate. Fellow artist John Young-Hunter, an English expatriate who traveled widely, recommended that Fechin visit the West and experience "real" America. In 1927 the Fechins moved to Taos, New Mexico, after spending the previous summer there in a house rented from socialite Mabel Dodge Luhan, who at the time was very active in the Taos art community and had encouraged a number of painters and writers to settle there.

As he had been intrigued with non-European cultures in Russia, so he was now attracted to the native people of New Mexico. The region's rugged, unspoiled scenery also appealed to his love of nature and in some respects reminded him of his homeland. Inspired by these recurring connections with Russia, Fechin produced a large body of work during the six years that he lived with his family in Taos.

Fechin apparently did not realize that the move to America might be permanent and often said that he intended to return to Russia one day when conditions improved. Meanwhile he created something of a Russian atmosphere in his home in Taos, where he spent the late afternoons or evenings carving furniture and sculpting decorative motifs in the woodwork and blending Russian design elements such as triptych windows and intricately carved doors with traditional Southwestern adobe construction. Woodworking came easily to Fechin, who as a youth had worked in his father's shop in Kazan carving and painting icons and decorating cabinetry.

While Fechin often kept to himself and rarely socialized, fellow artist John Young-Hunter was a good friend. Training as well as temperament tended to separate Fechin from his peers. He found it difficult to express himself in English and in particular to talk about art; he believed that what he had to say was nonverbal and best described in his pictures. When Fechin took time off from work, more often than not it was to try his luck at fishing.

Fechin's sojourn in Taos came to an end in 1933 when Alexandra filed for divorce. Leaving her with the house, Fechin took Eya and returned to New York City. Father and daughter later moved to California at the urging of Earl Stendhal, who represented Fechin through his gallery in Los Angeles.

Eya wrote an article that appeared in the November 1984 issue of America West magazine entitled "Teenage Memories of Taos." In it she related many incidents of her life at a time when, as she says, she passed from "being my mother's little girl...to my father's closest friend."

Renting a succession of studios in Pasadena and Hollywood, Fechin continued to work and teach as well as travel, visiting Mexico in 1936 and Bali in 1938. In 1947 he moved for the last time to Santa Monica, California, where on October 5, 1955, he died quietly in his sleep.

Eya returned her father's remains to Russia in 1976.

Despite his growing reputation and the obvious advantages of working in New York, Fechin found it hard to adjust to the pace of life in the metropolis. During his fourth year in America, he developed tuberculosis and on his doctor’s advice began a search for a more healthful climate. Fellow artist John Young-Hunter, an English expatriate who traveled widely, recommended that Fechin visit the West and experience "real" America. In 1927 the Fechins moved to Taos, New Mexico, after spending the previous summer there in a house rented from socialite Mabel Dodge Luhan, who at the time was very active in the Taos art community and had encouraged a number of painters and writers to settle there.

As he had been intrigued with non-European cultures in Russia, so he was now attracted to the native people of New Mexico. The region's rugged, unspoiled scenery also appealed to his love of nature and in some respects reminded him of his homeland. Inspired by these recurring connections with Russia, Fechin produced a large body of work during the six years that he lived with his family in Taos.

Fechin apparently did not realize that the move to America might be permanent and often said that he intended to return to Russia one day when conditions improved. Meanwhile he created something of a Russian atmosphere in his home in Taos, where he spent the late afternoons or evenings carving furniture and sculpting decorative motifs in the woodwork and blending Russian design elements such as triptych windows and intricately carved doors with traditional Southwestern adobe construction. Woodworking came easily to Fechin, who as a youth had worked in his father's shop in Kazan carving and painting icons and decorating cabinetry.

While Fechin often kept to himself and rarely socialized, fellow artist John Young-Hunter was a good friend. Training as well as temperament tended to separate Fechin from his peers. He found it difficult to express himself in English and in particular to talk about art; he believed that what he had to say was nonverbal and best described in his pictures. When Fechin took time off from work, more often than not it was to try his luck at fishing.

Fechin's sojourn in Taos came to an end in 1933 when Alexandra filed for divorce. Leaving her with the house, Fechin took Eya and returned to New York City. Father and daughter later moved to California at the urging of Earl Stendhal, who represented Fechin through his gallery in Los Angeles.

Eya wrote an article that appeared in the November 1984 issue of America West magazine entitled "Teenage Memories of Taos." In it she related many incidents of her life at a time when, as she says, she passed from "being my mother's little girl...to my father's closest friend."

Renting a succession of studios in Pasadena and Hollywood, Fechin continued to work and teach as well as travel, visiting Mexico in 1936 and Bali in 1938. In 1947 he moved for the last time to Santa Monica, California, where on October 5, 1955, he died quietly in his sleep.

Eya returned her father's remains to Russia in 1976.

Nicolai Fechin’s Artwork

Nicolai Fechin is one of the most important portrait painters of the 20th Century. In addition to his portraits, his paintings of Native Americans and of the New Mexico desert landscape are considered among his best works. Most visitors find something to intrigue or delight them in the works of Nicolai Fechin. The brilliance of his painting style and the bold imagery one encounters in his drawings is undeniably arresting. His exuberant use of line and color to define form creates an immediate impression of energy and purpose.

In his representations of people, one sees a remarkable ability to capture the essence of personality in paint or on paper, along with an intensity of feeling that reveals much about the artist's attitudes toward art and life. In pencil and charcoal drawings, oils, sculptures and photographs, Fechin's work brings to the viewer distinctly individual likenesses with an evocative flair that places him among the best portraitists of any time or place.

Fechin depicted himself, his father, and his wife and daughter, as well as the celebrities of his time and anonymous models who simply captured his attention, varying his approach to each according to the mood or character of his subject.

Eya recalled that he had difficulty in adjusting to "American-style" art. According to Eya, Fechin didn't like the power of art dealers and patrons. He believed that American artists were too fearful of losing control of their ideas and potential revenue, fostering a serious lack of exchange of ideas among artists. New Mexico encouraged him to paint landscapes. Like all the Taos artists, he appreciated the light of Taos. He thought Pueblo Indians possessed the same spirit as well as other qualities of the Tartars of his homeland. He began signing his name in English almost as soon as he arrived in the States, though he dismissed signatures as unimportant and said that a viewer should recognize his work by its execution. He always prepared his own canvases and seldom made preliminary sketches; most of his subjects were taken directly from life. He also maintained that the strongest and most lasting influences on any artist were those associated with the country of his birth. Perhaps with Fechin this proved to be true.

In his representations of people, one sees a remarkable ability to capture the essence of personality in paint or on paper, along with an intensity of feeling that reveals much about the artist's attitudes toward art and life. In pencil and charcoal drawings, oils, sculptures and photographs, Fechin's work brings to the viewer distinctly individual likenesses with an evocative flair that places him among the best portraitists of any time or place.

Fechin depicted himself, his father, and his wife and daughter, as well as the celebrities of his time and anonymous models who simply captured his attention, varying his approach to each according to the mood or character of his subject.

Eya recalled that he had difficulty in adjusting to "American-style" art. According to Eya, Fechin didn't like the power of art dealers and patrons. He believed that American artists were too fearful of losing control of their ideas and potential revenue, fostering a serious lack of exchange of ideas among artists. New Mexico encouraged him to paint landscapes. Like all the Taos artists, he appreciated the light of Taos. He thought Pueblo Indians possessed the same spirit as well as other qualities of the Tartars of his homeland. He began signing his name in English almost as soon as he arrived in the States, though he dismissed signatures as unimportant and said that a viewer should recognize his work by its execution. He always prepared his own canvases and seldom made preliminary sketches; most of his subjects were taken directly from life. He also maintained that the strongest and most lasting influences on any artist were those associated with the country of his birth. Perhaps with Fechin this proved to be true.

Taos Art Museum at Fechin House

227 Paseo del Pueblo Norte

Taos, New Mexico 87571

(575) 758-2690

[email protected]

Taos Art Museum is a tax-exempt non-profit, #85-0400684

227 Paseo del Pueblo Norte

Taos, New Mexico 87571

(575) 758-2690

[email protected]

Taos Art Museum is a tax-exempt non-profit, #85-0400684